.jpeg)

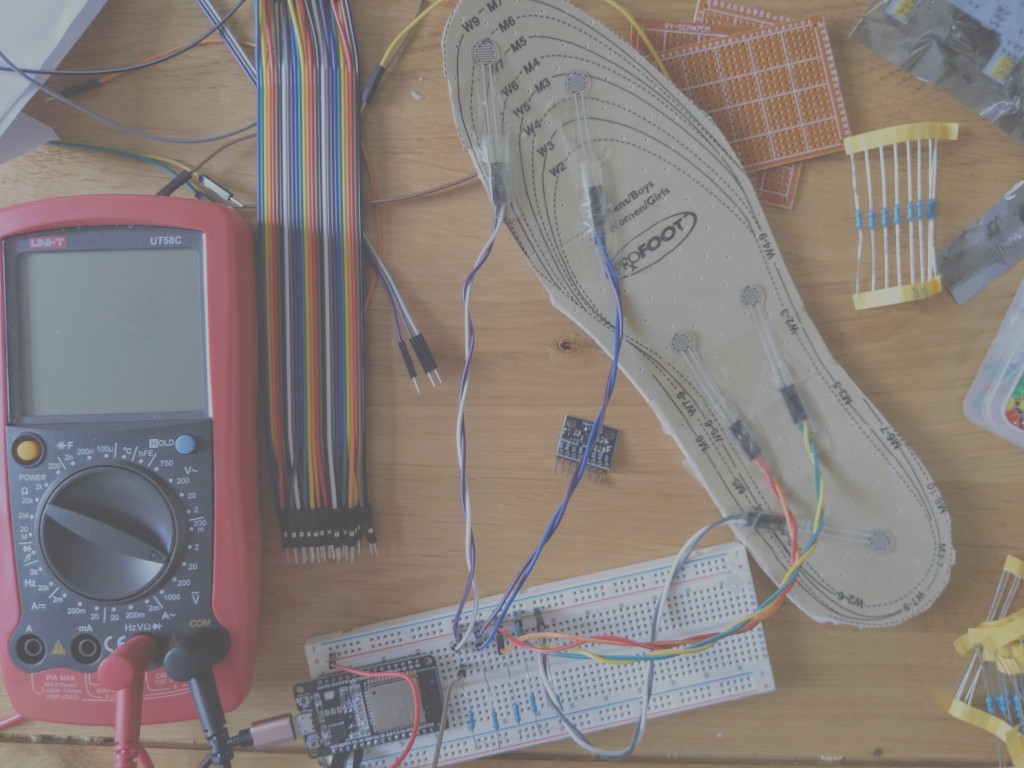

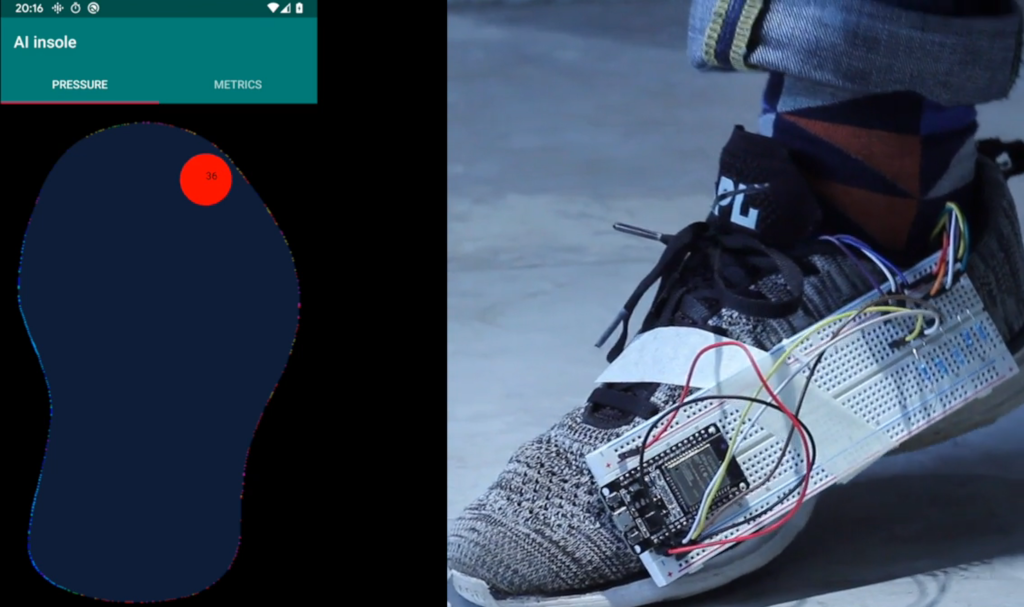

Lately I’ve taken to walking around Fuzzy Labs HQ with a breadboard taped to my shoe, pressure sensors embedded into an insole and a USB battery stuffed down my sock.

It’s unlikely to be the next fashion trend and I’ve been warned against wearing it to the airport, but this most amateur of electronics projects can stream data from sensors to my phone and tell me something useful about how I use my feet.

It’s remarkable how much is possible for only a small cost. The idea that anybody can buy some off-the-shelf components and construct their own wearable fitness tracker with with home-grown machine learning models is a testament to how accessible the tech is. This truly is AI (and IoT) for everybody.

Why build your own hardware?

Being the unrepentant nerd that I am, the pure joy of the tech is reason enough. Another motivation comes from improving my own health and well-being. I’ve got a slightly unusual gait and somewhat poor posture all of which inevitably leads to aches and pains - issues that I hope to correct with data.

Hardware isn’t something Fuzzy Labs specialise in. Yet modern AI applications are intrinsically linked with the so-called Internet-of-things, with intelligence appearing in our phones, watches, and home automation systems. So while our business may be software, an understanding of the hardware that sits at the edge is invaluable, and the best way to understand something is to build it.

How to put your shoes on the Internet

At the heart of the ‘smart insole’ is an ESP32 microcontroller manufactured by Espressif. This device is inexpensive, low-power, and supports Bluetooth and Wifi. It has a modest 520 KiB RAM and a 240 MHZ processor. The ESP32 is Arduino-compatible which means that we can use standard Arduino tooling and libraries with it.

Attached to a foam insole are 6 pressure sensors. Each pressure sensor is a variable resistor, which means that its resistance to current changes depending on how much pressure is applied.

Each pressure sensor is connected to one of the ESP32’s inputs via a voltage divider. In this case a voltage divider is simply a contraption we need so we can calculate the sensor resistance against a known reference.

Having built the prototype hardware we’ll want to run some software on it. There are two ways to program an ESP32, in both cases using C++:

- With the official toolchain, ESP-IDF

- Using the Arduino framework

The Arduino framework is a better choice because of its ubiquity and the wealth of online resources. Arduino code is portable to other Arduino-compatible hardware.

Next is the matter of tooling. Arduino tutorials invariably recommend using the Arduino IDE. And while this is a perfectly reasonable choice, I believe Platform IO is a better choice. Platform IO is a set of tools and an IDE designed for IoT development. The IDE itself is optional as the tooling works with other editors like Emacs and Vim too.

One important advantage of Platform IO is having proper dependency management, which is a must for any serious productionisable project.

Streaming sensor data with Bluetooth

The device uses Bluetooth Serial to send sensor readings to a paired Android phone. This is a simple Bluetooth library for the ESP32 which allows the sending and receiving of plain text messages over Bluetooth.

The Android app, written in Kotlin, is presently very primitive. It assumes that the insole has already been paired and awaits sensor readings. The sensor readings contain a timestamp, a sensor number and a pressure value.

Data aggregation

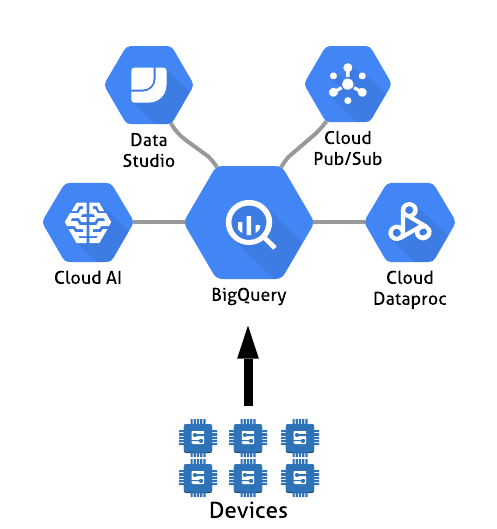

So far I’ve talked about hardware and software for data collection. If this device is to be useful to other people then we need to think about how aggregate data from many devices.

We’ll push the sensor readings to Google BigQuery. There are a few reasons for this: as well as being a powerful data warehouse with a convenient SQL interface and easy-to-use APIs, BigQuery acts as a hub to several more Google Cloud services:

- AI platform for training and deploying models.

- Data studio for building business intelligence dashboards.

- Cloud pub/sub, a powerful distributed message bus.

- Cloud Dataproc for managed Hadoop clusters.

Exercise modelling

There’s an abundance of uses for the data we collect from the insoles. Examples include assistance with exercise, physiotherapy, and intelligent fitness training. I’ll write a separate blog post dedicated to the data science involved in implementing some of these.

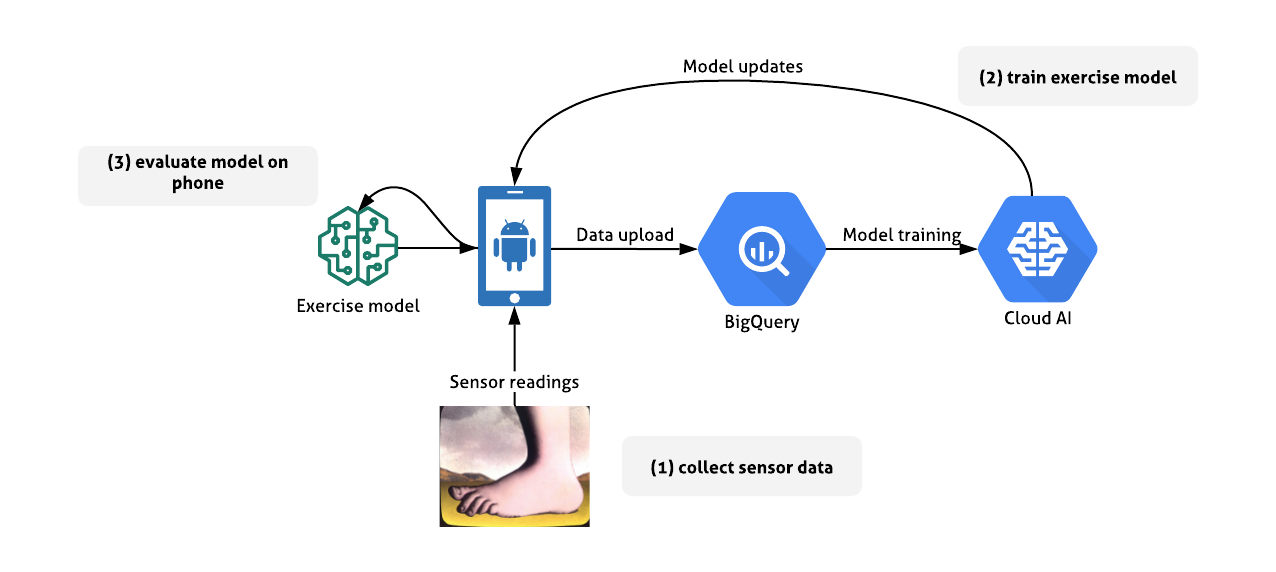

Before any machine learning can take place it’s important to establish some infrastructure that allows us to train and re-train models as well as testing and deploying them.

Data is ingested into BigQuery, and then models are trained on Google’s AI platform. The AI platform provides a set of APIs for training and deploying machine learning models using Python. It can be used with various machine learning frameworks including Tensorflow and Sci-kit learn.

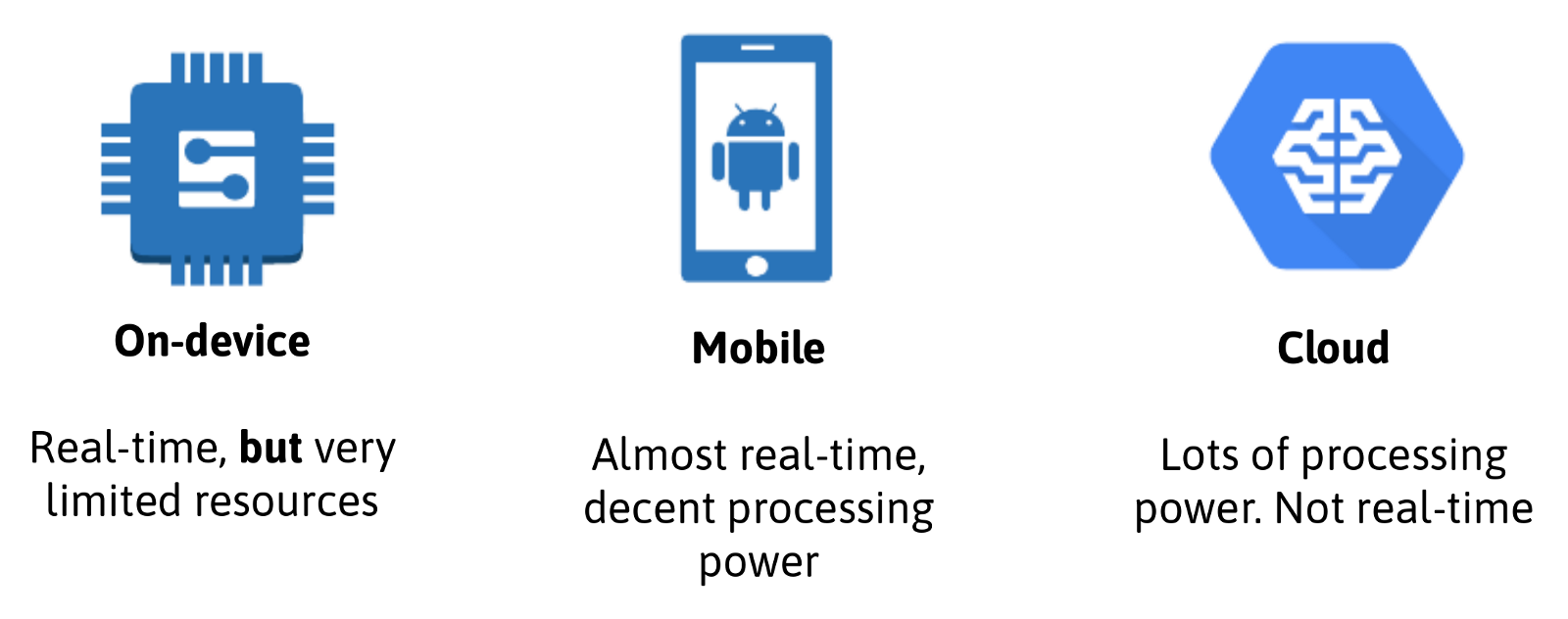

Cloud model training is very useful, because we have access to highly scalable compute power. However, hosting the trained models in the cloud may not be the best idea.

Suppose we have a model which takes the fifty most recent sensor readings as input and produces one of three labels as output: either running, walking, or idle. The latency of going to the cloud to query the model means that by the time we have a result it’s no longer relevant.

At the other end of the spectrum, running a model on the ESP32 gives the best responsiveness but with very limited computing power. The Android phone feels like a nice middle-ground. So we build, test and deploy our models from the cloud, but run them on the edge (to use the fashionable term).

The future

As a prototype, the hardware doesn’t need to be particularly resilient or ergonomic, but it’s an interesting exercise to see what a ‘real’ product might look like:

- All electronics contained inside a flexible insole to be inserted into the user’s shoe.

- Built-in battery and wireless charging.

- Easy bluetooth pairing to a smartphone.

- Exotic sensors, for instance a barometer to track elevation.

- Smart watch app.

This is all remarkably feasible. On the roadmap for this project is replacing the ESP32 and the big breadboard with a seweable electronics platform such as the Arduino Lilypad.

One difficulty remains with the battery, because traditional lithium ion batteries are famously prone to explosion when pierced, crushed, or used in a Galaxy Note 7. Thankfully there’s promising research concerning wearable batteries.

Contributing

We’re building open source tools for personalised fitness and healthcare devices and we’re keen for people to get involved in what we think is a pretty exciting area.

We’re grateful for the feedback we’ve received on social media, please keep it coming, and if you want to help out with hardware, software, data, design, or indeed testing some experimental devices, then let us know!

More information

We’ve recorded a couple of vlogs in which we discuss and demo the tech:

The source code is on Github here: https://github.com/fuzzylabs/ai-for-your-feet.

In a future blog post I’ll be looking in detail at how to train predictive models using data collected by the insole.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)